Attention struggles are not new. Long before smartphones and social media notifications, people sought creative — and sometimes extraordinary — ways to shut out distraction and concentrate on their work.

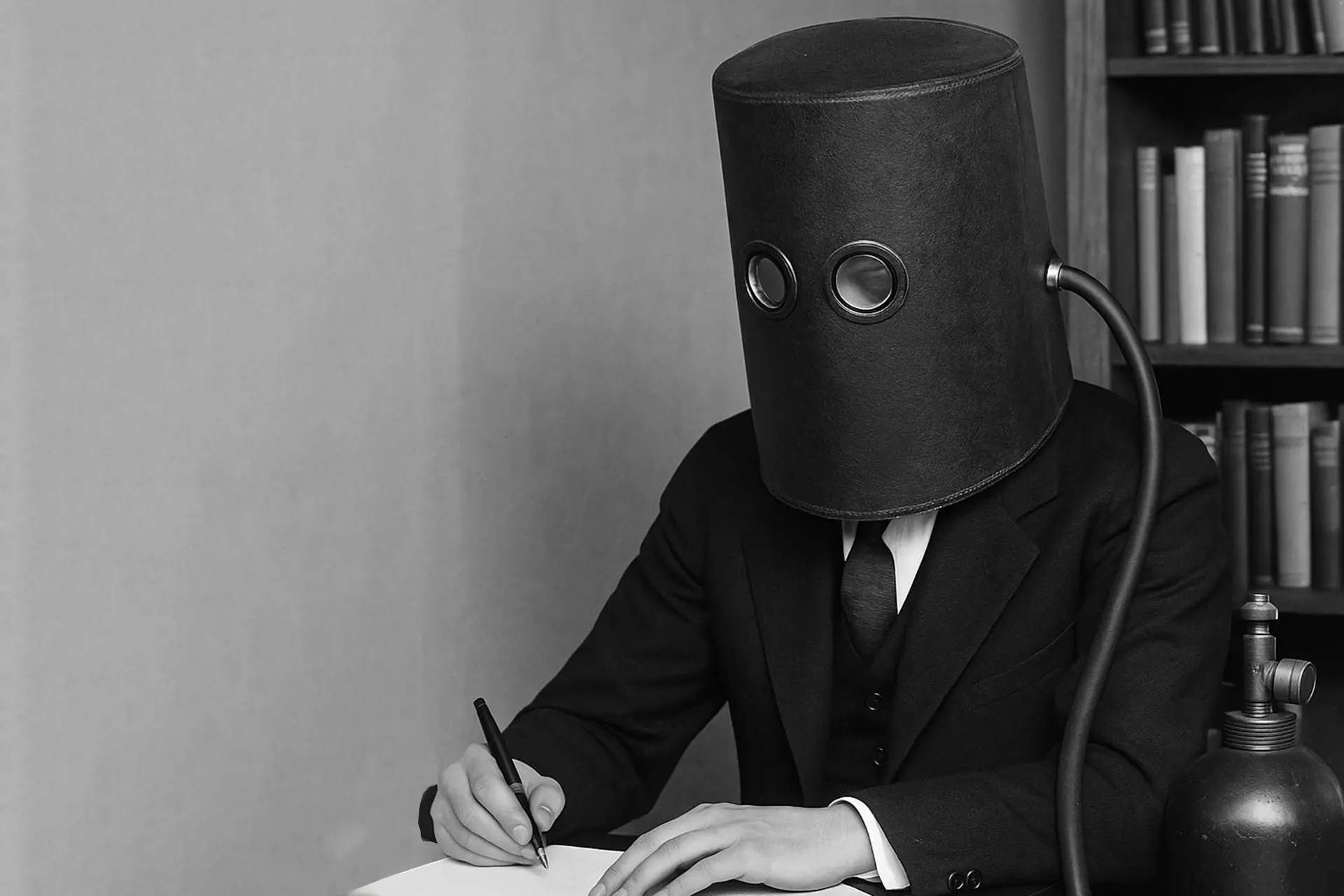

Among the strangest of these inventions is the Isolator Helmet, a 1920s contraption designed to help the wearer achieve total focus. It’s a striking reminder that humans have always grappled with the challenge of sustaining attention — a struggle familiar to anyone living with ADHD today.

This post explores the story of the Isolator Helmet and other early “attention aids”, and what they reveal about our evolving understanding of ADHD and concentration.

The Curious Case of the Isolator Helmet

In 1925, inventor and science fiction publisher Hugo Gernsback unveiled a device he called The Isolator. His aim was simple: to eliminate all distractions.

The helmet was made of wood, cork, and felt, and it completely enclosed the wearer’s head. Only two narrow slits in front of the eyes allowed a limited field of vision — just enough to see a page or typewriter. Sound was heavily muffled. Gernsback even experimented with adding an oxygen tube to help the user stay alert inside the sealed shell.

In theory, it was meant to create an environment of perfect concentration. In practice, it was cumbersome, uncomfortable, and totally impractical.

Even Gernsback admitted that users could become drowsy after 15 minutes, and only around a dozen units were ever made. Nevertheless, it captured the public imagination — both as a curiosity and as a commentary on our longing to control attention.

A Glimpse into Early 20th-Century Thinking

The Isolator emerged in an era fascinated by productivity, efficiency, and industrial progress. The 1920s saw new interest in self-improvement, time management, and the psychology of work.

At the time, “distraction” was viewed less as a neurological issue and more as a moral or personal failing. Inventors like Gernsback were responding to the same frustration that people with ADHD still voice today: “Why can’t I just focus?”

Without modern neuroscience, the proposed solutions were often mechanical rather than psychological — devices that sought to force attention through restriction rather than support it through understanding.

The Appeal — and the Problem — of Total Control

There’s something intuitively appealing about the Isolator’s promise: if only we could block every external distraction, perhaps focus would become effortless.

For people with ADHD, this desire for silence and control can feel familiar. The constant influx of sensory input — noise, movement, digital alerts — can be overwhelming, leading to frustration or mental fatigue.

But while environmental adjustments can help, total isolation is rarely the answer. Concentration doesn’t thrive under sensory deprivation. As Gernsback discovered, when the brain is cut off from stimulation, it tends to shut down rather than focus.

The Isolator Helmet symbolises the tension between external control and internal regulation — a lesson that remains relevant to ADHD treatment today.

Other “Anti-Distraction” Inventions Through History

Although the Isolator Helmet stands out for its eccentricity, it’s not the only attempt to engineer better focus.

- Early “Thinking Caps”

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, several companies marketed “thinking caps” that claimed to stimulate the brain or aid concentration. Most were gimmicks, but they reflected a growing belief that attention could be improved through physical means — from electrical stimulation to posture correction.

- Sensory Control Rooms

Writers and scholars have long recognised the value of solitude. Medieval monks studied in private cells; later, scientists and philosophers built dedicated study rooms with thick walls and minimal distractions. These early “quiet spaces” mirror today’s understanding that environmental control supports executive function, especially for those with ADHD.

- Mid-Century Productivity Tools

By the 1950s and 60s, focus aids became more subtle: ergonomic desks, metronomes for timed work sessions, and later, time-management methods like the Pomodoro Technique (developed in the 1980s). Each aimed to improve focus through structure rather than isolation.

- Modern Descendants

Today’s equivalents — noise-cancelling headphones, white-noise apps, and digital distraction blockers — share DNA with the Isolator Helmet, but they emphasise balance and autonomy. Instead of forcing isolation, they empower the user to choose how and when to reduce stimulation.

What These Inventions Tell Us About ADHD

Although ADHD wasn’t formally recognised until the 20th century, people have always experienced variations in attention, impulsivity, and emotional regulation.

The Isolator Helmet and similar inventions highlight several enduring truths:

- Distraction Is Human

Everyone struggles with focus at times. But for people with ADHD, the difference lies in neurological wiring — not motivation or willpower. The brain’s networks for attention and inhibition work differently, making it harder to filter irrelevant input or sustain focus on low-interest tasks.

- Environment Matters

Many people with ADHD find that noise, visual clutter, or interruptions rapidly derail their concentration. This is why supportive environments — quiet zones, structured routines, task lists — can make such a difference. The Isolator was an extreme version of this principle, but modern adaptations (like noise control or minimal workspace design) are evidence-based.

- External Tools Have Limits

Whether it’s an oxygen-piped helmet or a digital app blocker, external tools can only do so much. Effective ADHD management involves addressing the underlying self-regulation difficulties through therapy, coaching, medication, and lifestyle strategies.

- Creativity Often Co-exists with Distraction

Interestingly, Gernsback himself was a visionary — the founder of modern science fiction. Many people with ADHD share this pattern: intense imagination and innovation paired with inconsistent attention. What we call “distraction” sometimes fuels creativity.

From Isolation to Understanding: The Shift in Perspective

Modern psychology views attention not as something to control by force, but as something to understand and work with.

We now know that ADHD involves differences in executive function, motivation, and dopamine regulation. Strategies focus on self-knowledge and compassionate structure, not punishment or deprivation.

Instead of helmets, we now talk about:

- Task chunking (breaking work into manageable pieces)

- Time awareness tools (timers, visual planners)

- Behavioural techniques to build routine

- Psychoeducation to reduce shame and increase self-understanding

- Therapeutic approaches like CBT, ACT, or Compassion-Focused Therapy

- Medication, which can support focus and emotional regulation

These evidence-based methods recognise ADHD as a neurodevelopmental condition — not a moral weakness or character flaw.

Why the Isolator Still Captures Our Imagination

Nearly a century later, images of the Isolator Helmet still circulate online — part humour, part fascination. There’s something oddly relatable about the idea of wanting to shut out the world just to think.

For clinicians, the Isolator offers a useful metaphor: it illustrates both the intensity of the struggle for focus and the risk of overcorrection. In ADHD treatment, the goal is not to isolate but to integrate — helping individuals find focus within their environment, not outside it.

Lessons for Today

- Attention tools should support, not punish.

The best strategies feel empowering, not restrictive. - Understanding beats control.

ADHD management starts with insight — understanding how attention works for you, and where support is needed. - Balance stimulation and calm.

People with ADHD often focus best with the right level of stimulation — music, movement, or interest. Too little can be as challenging as too much. - Compassion is key.

From early “thinking caps” to today’s productivity apps, the search for focus has often been framed as self-improvement. For people with ADHD, it’s really about self-acceptance and sustainable change.

Practical Takeaways

If you or someone you know struggles with focus or distraction:

- Experiment with environmental supports: noise-cancelling headphones, tidy workspace, or structured routines.

- Use short bursts of effort followed by rest — attention works best cyclically.

- Avoid harsh self-criticism; attention difficulties are part of ADHD’s neurological profile.

- Seek professional support if focus problems cause distress, burnout, or low confidence.

You don’t need a helmet to find clarity — you need understanding, strategy, and kindness.

Final Thoughts

The Isolator Helmet stands as both an oddity and a mirror: a reminder of how far we’ve come in understanding the human mind.

Where once people sought mechanical solutions to “fix” distraction, we now recognise ADHD as a neurodiverse way of experiencing the world — one that can bring both challenges and remarkable strengths.

Focus is not about cutting out the world entirely. It’s about finding the right conditions, tools, and mindset to thrive within it.

Ready to Take the Next Step?

If attention challenges, distraction, or focus difficulties are affecting your wellbeing, there is evidence-based help available.

As a Clinical Psychologist specialising in ADHD assessment and treatment, I work with adults to understand their unique attention patterns and build practical, compassionate strategies for focus and emotional regulation.

You can get in touch to arrange a confidential consultation and take the first step towards greater clarity and calm.

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2018). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management (NICE guideline NG87).

- NHS. (2024). Overview: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). NHS.uk

- “The Isolator” (helmet). Wikipedia

- Open Culture. (2021). The Isolator: A 1925 Helmet Designed to Eliminate Distractions & Increase Productivity. openculture.com

- Paleofuture. (2013). This Extreme Invention From the Grandfather of Sci-Fi Was Supposed to Cut Out Distractions. paleofuture.com

- Edelman, N. (2020). Supporting Relationships When One Partner Has ADHD. British Psychological Society, Division of Clinical Psychology.